December 4, 2018

By Marie Zhuikov

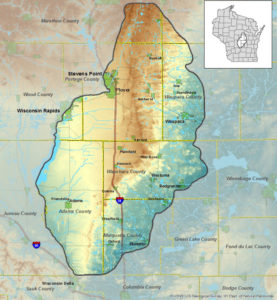

Thanks to its sandy soil, the Central Sands region in Wisconsin is a great place to grow vegetables. However, this area north of Wisconsin Dells is also known for water quantity issues. Lakes and rivers are slowly disappearing for complex reasons, one being the high-capacity wells that provide water for irrigation.

Now the beleaguered area is also facing water quality issues from the longstanding use of fertilizer on its cropland.

Two Water Resources Institute researchers are working on a project that will help farmers in the Central Sands better manage their nitrogen fertilizer use and improve water quality and quantity in a changing climate.

Chris Kucharik, professor in the Department of Agronomy and the Nelson Institute Center for Sustainability at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Matthew Ruark, associate professor in the Department of Soil Science and extension state specialist also at UW-Madison, are conducting their work at several farms and at the Hancock Agricultural Research Station in the center of the Central Sands region.

One focus of their project is the amount of nitrogen contained in irrigation water even before any fertilizer is applied. Kucharik and Ruark plan to develop measures and computer models that can guide farmers in their water and nutrient management plans.

“The whole idea is to give growers and extension folks a more concrete number they can work with so that they can adjust the amount of fertilizer they’re applying to accurately account for the amount of nitrogen that’s coming through the water,” Kucharik said. “Any little bit of nitrate that we can prevent from making its way down into the groundwater system is a win for the environment as well as farmers in terms of saving money.”

The sand that makes the soil so good for growing potatoes, sweet corn, peas and snap beans also requires frequent irrigation and fertilization. Bacteria in the soil convert the ammonia and nitrogen from fertilizers into the harmful nitrates sometimes found in irrigation water and drinking water from wells.

“The farmers have really struggled with how to minimize the amount of nitrates that are leaving the soils and making their way into the groundwater system,” Kucharik said. “We’ve known this for decades. Given the sandy soils – they’re not really great for holding onto water. Things drain quickly through them.”

Kucharik explained the long history of human health problems caused by people drinking water with an elevated concentration of nitrate. “It’s not healthy for pregnant mothers, it’s not good for young children. The condition of blue baby syndrome is often attributed to this problem,” he said.

“It’s really unfortunate that we’ve gotten to the point where if you’re on a private well, no matter where you are, you need to be concerned about this just because of potential ramifications to our health,” Kucharik said.

Nitrate is Wisconsin’s most widespread groundwater contaminant. The threshold for nitrates that the Environmental Protection Agency considers safe is 10 parts per million. A 2018 report by Wisconsin’s Groundwater Coordinating Council found that about 10 percent of private wells sampled in the state exceed these standards. At least one homeowner’s well in the Central Sands district tested at 45 parts per million – more than four times the safe limit.

Even rainwater is not immune from human influence where nitrates are concerned. A small quantity can be found in it, especially in urban areas where emissions from cars, electric utilities and industrial boilers are a source. Kucharik and his team are collecting rainwater samples in addition to weekly irrigation water samples to have a complete picture of nitrogen inputs to the land.

According to previous research by Kucharik and information from the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, the Central Sands area has already experienced a trend toward warmer nights, along with a 15 percent increase in annual precipitation and a longer growing season by approximately two weeks. By mid-century, the annual mean temperatures are predicted to increase by 2.6 to 3.6 degrees Celsius and the growing season is projected to lengthen by yet another two weeks.

“The bottom line is that it’s going to become more challenging in the future for farmers to grow crops because warmer temperatures mean an increased demand for water that will need to be applied at the same time as the weather becomes more variable, particularly how precipitation is delivered,” Kucharik said. “It’s going to be more challenging for growers to keep nitrogen in the cropping system and not have it leach out.”

The researchers plan to develop a modeling tool as a way to explore various climate scenarios so that growers know what to expect. They want to develop management options that hit a “sweet spot” where water and nitrogen use efficiency are maximized in the Central Sands without significant reductions in yield.

Once they have findings to distribute, the team expects to present them at meetings of a water task force that is part of the Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association (WPVGA). The WPVGA also hosts an annual conference where researchers can reach an audience of growers that can number up to 500.

“It’s not often that you get a chance to address that many people on a variety of topics,” Kucharik said. “The WPVGA is a close-knit group and they’ve supported university research for many years. They’re a great player.” This group also provided seed money for the project.

Outreach is Ruark’s speciality. He is an extension agent who works directly with farmers around the state. Kucharik has no doubt that the research results will filter through the community quickly and easily thanks to Ruark.

Kucharik is excited about this project. “It’s very much a tight coupling between doing field work on the landscape, working with the growers, and connecting that to modeling to help us understand how things will function differently in the future so we can help people get ahead of the curve and help farmers think about potential adaptations they might need to make. The last thing we want is for is for environmental problems to become so bad that the state has no choice but to start regulating nutrient and water management in ways that growers are not used to. That could mean great economic hardships in a variety of ways,” he said.