Nov. 15, 2019

By Jennifer A. Smith

As Yogi Berra famously said, it’s déjà vu all over again. Carolyn Voter, a familiar face around the University of Wisconsin-Madison Aquatic Sciences Center (ASC), is reprising her role as the Wisconsin Water Resources Science-Policy Fellow. The fellowship is jointly supported by the Water Resources Institute (part of the ASC) and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

It’s a role Voter first filled in 2015-16, when the fellowship was being piloted and designed for a graduate student. Voter was working on her Ph.D. in urban hydrology at the time. Now, with her doctorate freshly in hand, Voter is embarking on a new fellowship, which has been reconfigured for post-doctoral or post-master’s applicants. “I’m doubly lucky to do this a second time,” said Voter.

Voter began her current tenure in September and works in downtown Madison at the DNR’s Drinking and Groundwater Bureau and Water Use Section.

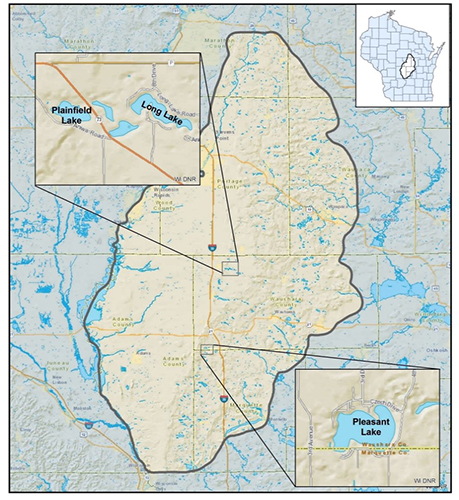

For the next year, her task will be to shed light on a topic of great interest to residents and stakeholders in the Central Sands region. Along with a team of about 40 others, Voter is working on the Central Sands Lake Study, which focuses on the interactions between groundwater and three lakes in the region, and the impact of high-capacity wells on those lakes.

In 2017, the Wisconsin Legislature tasked the DNR with conducting this study as part of the passage of Act 10. In particular, the DNR was charged with looking at three Waushara County lakes—Pleasant, Long and Plainfield—and determining whether groundwater withdrawals are having a significant impact on them, or could have a significant impact in the future.

The study must be completed by June 2021, when the DNR will present its final report to the Legislature. In that report, the DNR may recommend special measures to prevent or remedy a significant reduction in lake levels, per the charge from the Legislature.

The study team spans multiple DNR units, the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, the United States Geological Survey, and academic researchers from UW-Madison, UW-Stevens Point and other schools.

Not all water is the same

The Central Sands portion of Wisconsin is one of the most heavily irrigated regions in the state. In 2018, high-capacity wells drew 14.5 billion gallons of water for agriculture in Waushara County. Potatoes, field corn, soybeans, green beans, sweet corn, peas, carrots and other vegetable crops are grown in the area.

Voter’s main objective is to decide what constitutes a “significant impact” from a scientific standpoint. She will consider three main impact areas: water quality, recreational use (such as boating and water skiing) and aquatic life.

“What I’m working to come up with is a method for determining how those three areas would be impacted based on lake levels and how much groundwater inflow those lakes are receiving,” said Voter.

Drawing large amounts of groundwater from area wells may result in lowered lake levels, since there is less groundwater available to feed into the lakes.

The fact that groundwater and lake water have markedly different water chemistry adds to the complexity of this interplay between groundwater use and groundwater movement into lakes and lake levels. “As you change how much groundwater is flowing into the lakes, you may also change what the water chemistry is like, and the water quality as well,” noted Voter.

She is also working to characterize the lakes as they are now, so there is a solid foundation for computer modeling exercises to show how changes in groundwater might affect the lakes.

Engagement is essential

While Plainfield Lake lies next to a lot of DNR land, Long and Pleasant Lakes have homes along their lakeshores. Naturally, homeowners are one stakeholder group with an interest in the study’s findings, as are area farmers, such as those in the Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association.

As the study progresses, the DNR will continue to reach out to interested parties through a variety of means, such a webinars that are expected to take place next spring or summer, and conference presentations to lake managers and academic researchers.

“The DNR is really conscious of the different perspectives that these different stakeholder groups have, and they are being very intentional in how they’re reaching out to the public and providing updates about what we’ve found so far. Continued engagement with the community is a strong part of this study,” commented Voter, “and something that will be helpful for me to have more experience with as well.”

There will also be public hearings before the final report is delivered to the Legislature.

Research for real life

As a newly minted Ph.D. with a one-year fellowship commitment, Voter is beginning to mull over what her next professional step will be.

While both academia and government service have their appeal, “The constant is that I like doing research where I can see how it’s affecting people’s day-to-day lives. With this current project, we’re working on understanding how management decisions affect lake levels, and what options we have for managing those resources more sustainably.”

For now, she is enjoying the collaboration that comes with being part of a large team; it’s a change of pace from the small-team research of her grad student days.

Said her colleague Katie Hein, a water resources management specialist with the DNR, “Carolyn is a quick study, and she is very skilled at writing code for sophisticated data analyses. These traits are critical for the problem at hand, as there is not a cookie-cutter solution.”

Voter is excited that the Central Sands Lake Study is being viewed by other states as a new model. “There’s not really a roadmap for how you think about the impact of groundwater withdrawals to lakes, certainly from a management and policy perspective. Lots of states are looking to us, and that’s an exciting place to be.”