Feb. 27, 2020

By Marie Zhuikov

Several graduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison were part of a research team that found levels of radium in groundwater from public water supply wells in much of Wisconsin have risen over the past 18 years.

Madeleine Mathews, Amy Plechacek and Marie Dematatis conducted their study on this natural contaminant under the guidance of Matthew Ginder-Vogel, associate professor in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at UW-Madison, by putting a new spin on groundwater data collected by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

Their findings were published Feb. 20 in “AWWA Water Science,” a journal of the American Water Works Association. (“Spatial and temporal variability of radium in the Wisconsin Cambrian-Ordovician aquifer system.”)

According to the National Academy of Sciences, radium is of concern because long-term exposure to elevated levels of this contaminant in drinking water may result in an increased risk of bone cancer.

Radium occurs naturally in some Wisconsin groundwater. As the water moves through the underground aquifer system, minerals and other elements, including radium, dissolve out of the rock and into the groundwater. Some rocks transfer radium more effectively than others into groundwater.

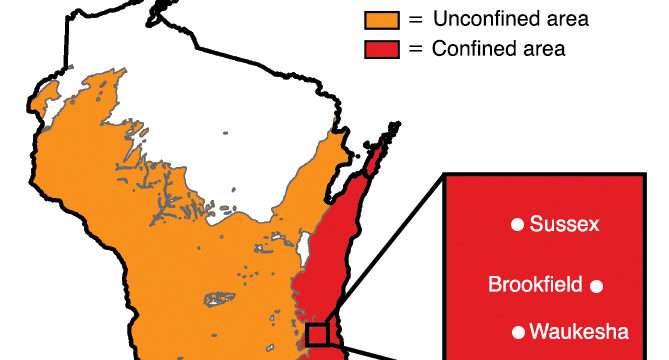

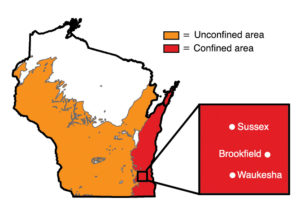

In Wisconsin, the highest radium levels occur in water from two types of rock aquifers: the deep sandstone in Wisconsin’s eastern quarter and the crystalline granite found in the north-central part of the state. Water softeners can lower radium levels in drinking water, as can diluting it with water containing lower radium concentrations.

The students took information from a long-term, publicly available dataset by the DNR and examined the numbers from the year 2000 through 2018 for trends in radium levels, focusing on the most-problematic deep sandstone aquifer.

Mathews explained what conditions result in elevated radium in groundwater. “In the very eastern part of Wisconsin, there’s a thick shale layer that acts as a regional confining unit, separating the deep Cambrian-Ordovician bedrock below from the shallow Silurian bedrock above. In the rest of the state, you don’t have this really thick shale layer, so we call it regionally unconfined.”

Previous studies have shown that elevated radium occurs in groundwater that is old, has elevated dissolved solids or is anoxic. Mathews said all those conditions are found below the regional confining unit in eastern Wisconsin.

Previous studies have shown that elevated radium occurs in groundwater that is old, has elevated dissolved solids or is anoxic. Mathews said all those conditions are found below the regional confining unit in eastern Wisconsin.

“We found that, overall, the radium levels are increasing more in the confined region in the eastern part of the state,” said Plechacek. “However, we still see increases in radium from 2000 to 2018 in the rest of the state, regardless of if there is a confining unit or not.”

The average radium level in the confined region increased from 5.5 to 7.9 picocuries per liter (pCi/L) over this time period, and the level in the unconfined region increased from 4.8 to 6.6 pCi/L. The maximum contaminant level set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for drinking water is 5 pCi/L.

Mathews said they aren’t sure why the increase is happening. “We have all this data but it doesn’t give much of an explanation,” she said. “It’s just kind of the tip of the iceberg, so we’d like to use this dataset to explore that in another study.”

The team also looked closely at radium trends over time in public wells from three communities: Sussex, Brookfield and Waukesha. Although these cities in eastern Wisconsin are near each other, the researchers found variable trends.

“For Sussex and Brookfield, radium levels appear to increase over the study period,” said Plechacek. “For Waukesha there is an overall decrease in radium, although levels in most of their wells remain above the maximum contaminant level for safe drinking water.”

Waukesha sought a new drinking water source mainly because of elevated radium, and is in the process of switching from groundwater to water pumped from Lake Michigan. Construction of the new system could begin this year. The switch required permission from the governors of the other Great Lakes states and provinces, causing much controversy and discussion when it was brought up in 2016.

Mathews said their research project was the result of collaboration between many different groups at the university and also state agencies. She said their methods are applicable to similar datasets in other states. “There are other groups doing similar things across the country. These long-term water quality monitoring datasets are definitely a powerful tool. You can filter through them and get useful information out of them.”

Funding for this project was provided by the Wisconsin Groundwater Research and Monitoring Program and the Wisconsin DNR. The University of Wisconsin Water Resources Institute is part of the groundwater research and monitoring program.