Feb. 15, 2022

By Jennifer A. Smith

Winter in Wisconsin is road salt season, as workers try to ensure our roadways are as safe and non-slippery as possible during bouts of snow and ice.

Yet, as public information campaigns like Wisconsin Salt Wise point out, the application of road salt comes with trade-offs. Salt, or sodium chloride, can harm freshwater ecosystems. According to Salt Wise, “It only takes one teaspoon of salt to pollute five gallons of water to a level that is toxic to native aquatic organisms.” It can also impact drinking water.

And, as research currently underway at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) is uncovering, increased levels of chloride from road salt can persist in surface waters even in the summer—when no salt is being applied—because it appears to be stored in groundwater.

The study, “Mass Discharge of Road Salt via Groundwater to Surface Waters in Southeastern Wisconsin,” is investigating two sites in Racine County along the Root River: one urban, the other rural. Led by Assistant Professor Charles Paradis, this work is being funded by the University of Wisconsin Water Resources Institute in its 2021-23 cycle.

Working with Paradis are graduate student Leah Dechant and, through UWM’s Support for Undergraduate Research Fellows (SURF) program, several undergraduate students.

Ultimately, the work that Paradis and his student team are doing can help policy makers make the best possible decisions when it comes to road salting practices. Said Paradis, “Clearly, road salt is good for public safety, but it may not be so good for environmental health, so where’s that balance? If we give this information to those who set that policy and practice road salt application, maybe they can do so in way that is best suited to balance public safety and environmental health.”

Paradis first became interested in the issue after a 2019 talk given by Cheryl Nenn of Milwaukee Riverkeeper about her annual Milwaukee river basin quality report. Nenn also pointed Paradis to a report put out by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC). Laura Herrick, a SEWRPC environmental engineer, had written about road salt in river water and noted elevated chloride concentrations in the Root River during the summertime.

As Paradis recalled, “They proposed the hypothesis that road salt is being stored in the groundwater that is connected to the river, and the groundwater serves as a continuous, long-term source for chloride to enter the river.”

What the SEWRPC observation needed was better testing, and Paradis was eager to dig further. He needed high-frequency samples of chloride and flow measurements at multiple locations along the Root River in the summer. That’s where graduate student Dechant and the undergraduates have been a major asset.

Field sampling began in July 2021. From July to September, surface water samples were collected three days per week. Moving into the fall, sampling shifted into a biweekly mode using the same locations and procedures.

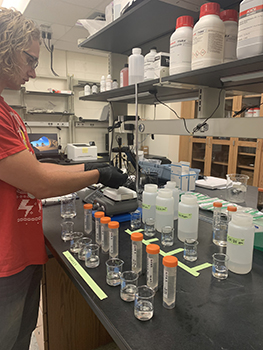

Half of the samples undergo high-level isotopic and chemical analysis by Timothy Wahl, an associate investigator on the project, at the UWM School of Freshwater Sciences. The other half of the samples are subject to benchtop pH and alkalinity low-level testing in the Paradis lab.

For Dylan Childs, one of the undergraduates who has worked on the project, the process has been rewarding. “’I’ve really come to enjoy the scientific method and research in general,” he said. “This was probably the first research project where I got to go out in the field, and it was a lot of fun having that hands-on experience, as well as going in to the lab, too. I felt so much more involved.”

Added Childs, a senior geology major from Stoughton, “Having this additional research experience as an undergrad has definitely helped me home in on what I want to do with my future.” Undergraduates Autumn Routson and Samuel Sellars have also contributed to the project.

In addition to people power, the research is aided by technology. United States Geological Survey (USGS) gauging stations are located at the study sites. These stations beam publicly accessible data, including flow data, to the internet. Continuous monitoring devices on loan from SEWRPC have also helped; these record temperature, conductivity—a proxy for chloride—and depth round the clock.

Through data collected from the USGS gauging stations, the loaned monitoring devices and water samples collected in the field, the team is capturing a much richer picture of what’s actually happening in the Root River. Paradis has noted that chloride concentrations in the river water have remained relatively constant—even when flow has increased and one might expect to see dilution as a result. This lends credence to the hypothesis that chloride is being stored in groundwater, providing a continuous source.

While almost a year and half of the project period still remains, Dechant will present the team’s findings so far in a poster session at this year’s conference for the Wisconsin Section of the American Water Resources Association (AWRA), which will take place March 10-11.