The 1980s called, they want to check in on their atrazine-use policy.

While it can feel retro to talk about this herbicide that captured Wisconsin headlines over four decades ago, it remains a highly relevant topic in 2024.

Sam Brockschmidt is eager to explore that relevancy through a brand-new Wisconsin Water Resources Science-Policy Fellowship focused on evaluating existing atrazine data, gathering new data and analyzing current restrictions on atrazine use in parts of the state known as prohibition areas. In short, he said he will attempt to, “figure out if we have been improving groundwater quality in a comprehensive way.”

Groundwater monitoring in the 1980s and ‘90s found atrazine, used for killing weeds in farmers’ fields, was responsible for groundwater and drinking water contamination. In March 1991, the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection enacted its first restrictions on atrazine use, establishing an atrazine management area and six prohibition areas. That initial approach has now evolved into outright prohibition areas, which have grown to 101, representing about 1.2 million acres. These areas where no atrazine can be applied on corn and other crops are located primarily in central and southern Wisconsin but do exist elsewhere. In fact, 35 out of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have a prohibition area.

Brockschmidt’s project will quantify how a prohibition area is effective and how it’s not and will explore implications of both of those conditions.

If an area is effective, that could prompt calls to lift the restrictions. That, said Brockschmidt, is tricky. “Even if the prohibition area seems to be working, it’s not necessarily that we’ve solved the problem. Because the prohibition area is keeping the atrazine concentration in check, but if we went back to the way that things were before the prohibition area, we might just go back to the same problem we’ve had before where so much atrazine was getting into our drinking water. It’s a very complicated issue that this project is tackling. But step one is just figuring out what data we have and are these prohibition areas actually effective.”

On the flipside, an ineffective zone is likely that way due to a multitude of factors. For example, he noted, “You’d think that if you stopped using atrazine in a place and then you keep testing your groundwater eventually your groundwater will have lower concentrations.” However, he cited one of Mother Nature’s maxims: water goes wherever it likes and doesn’t respect an artificial boundary like a prohibition zone.

“You might have a prohibition area on one side of the road and then on the other side of the road they’re just free to use as much atrazine as they want within the scope of the current regulations on it. So, the atrazine that is applied outside of the prohibition areas may get into prohibition areas. It all has to do with soil type and the hydrogeology of the subsurface,” he said.

Earlier this month Brockschmidt, who has a master’s degree in geoscience from UW-Madison, began his one-year fellowship that is sponsored by DATCP and the University of Wisconsin Water Resources Institute. “This is our first time creating such a position,” said Carla Romano, groundwater specialist with DATCP. “We believe that partnering with a university is an excellent way to attract individuals interested in research careers with significant societal impact. This project requires someone who is dedicated to such a path, and a university partnership is the perfect avenue to find and nurture this talent.”

For his part, Brockschmidt said the opportunity will afford him the chance to evaluate the two long-term paths he faces. At the fellowship’s conclusion, he will either pursue a career in a state agency or one in academia.

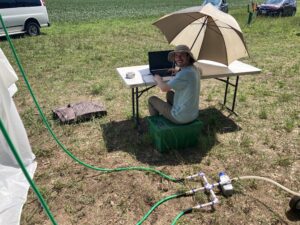

In the meantime, he said one appealing aspect of this fellowship is the chance to engage with people about atrazine. It’s a product that is useful in agriculture. It is relatively inexpensive and highly effective, which could improve crop yields and increase income. But it does have deleterious effects on the water people drink. “Part of the project is that I’m going to be going out and collecting new samples of people’s drinking water. I’ll be at their homes so I’m going to be interacting with people, maybe learning about them and writing their stories of how these prohibition areas impact them,” said Brockschmidt. “I’m really excited to get to know some people here in Wisconsin and learn what their perspectives are from the other side of these regulations.”

He will also enjoy free time in the coming year, engaging in outdoor pursuits like camping and hiking. In fact, immediately before heading to the Madison headquarters of DATCP where he will be stationed, Brockschmidt slingshot from a 10-day hiking trip in Japan, to an overnight in Chicago and then the following day departed for Scotland on a college-sponsored trip. In that compressed time span, he hiked divergent terrains, both in the name of reveling in the outdoors.